At some point over the last year, almost every founder or CTO I speak with says the same thing.

AI works.

The demos are impressive.

The answers sound confident.

And yet, something feels off.

The system doesn’t crash. It doesn’t obviously fail. But decisions based on it feel risky. Teams double-check results manually. Costs grow quietly in production. Trust never fully settles. Not because the AI is stupid, but because no one can clearly explain why it reached a particular conclusion.

A few weeks ago, our CTO asked me to write an article about ontology.

Not about AI in general.

Not about LLMs, agents, or RAG.

Ontology.

My first reaction was resistance. I’m not an engineer. I don’t write academic articles. My role sits somewhere else, at the intersection of product, delivery, and growth, in that uncomfortable space between “technically correct” and “business-acceptable”.

But one thought kept coming back.

If ontology matters only to engineers, then it doesn’t matter at all.

If it matters to business, I should be able to understand it without pretending to be someone I’m not.

So instead of opening Google or reading research papers, I did something else. I went to our AI team. Then to projects where ontology was already running in production. Then to the people who had to explain AI behavior to clients when things didn’t quite add up.

I didn’t ask “what is ontology”.

I asked a simpler question.

What breaks without it?

What I expected was a technical discussion. What I got was a pattern.

At the beginning of most AI projects, the system behaves like a smarter version of search. Documents go in, answers come out. RAG works well. It’s easy to demo. For a while, everyone is happy.

The problem starts later, quietly, when the system is no longer asked to retrieve information, but to understand it. To connect facts across documents. To summarize globally, not locally. To explain relationships that are never written explicitly anywhere.

This is the moment where AI stops being a tool and starts pretending to be a thinker.

And that’s where “just LLM” or “just RAG” often hits a wall.

Not because it can’t answer.

Because it can’t reason reliably when the truth is scattered across the corpus.

The usual fix is brute force. More chunks. More documents. More tokens.

Accuracy improves a bit.

Costs explode.

Noise replaces signal.

And that’s when I heard a sentence that made the whole topic click.

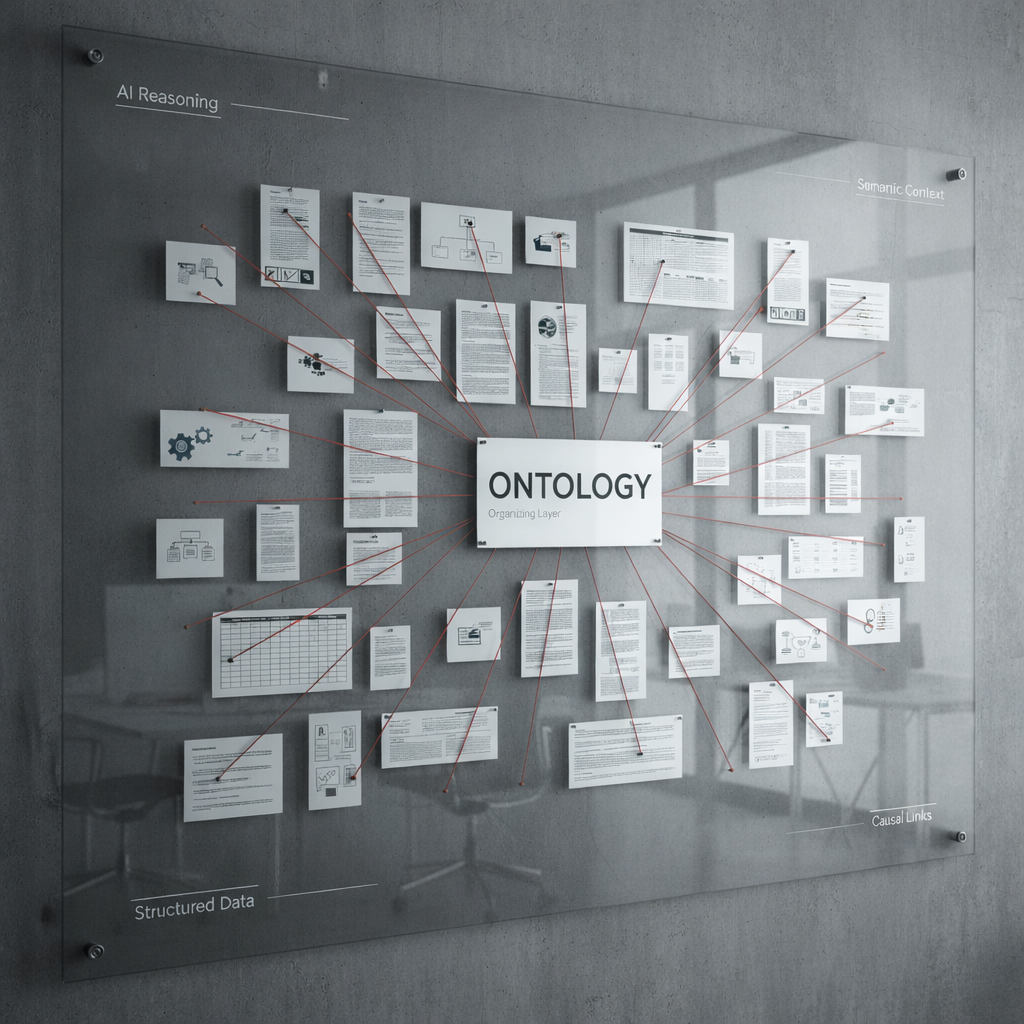

One developer explained it to me using an image I could not forget. They were testing a case involving a large financial investigation. Thousands of documents. Transactions across countries. No obvious links. When they built a structured graph of entities and relationships, something finally emerged.

“It’s like in detective movies,” he said. “A board on the wall. Cards everywhere. And strings connecting things that don’t look connected at first.”

Without structure, AI reads pages.

With structure, it sees systems.

Ontology, in this context, is not an abstract concept. It is the decision to define what those cards are allowed to be, and what those strings actually mean.

This is where a lot of people get confused, so I’ll say it plainly in founder language.

RAG is good at finding relevant text.

But when your real problem is: “what is the relationship between these entities across documents, and what does it imply”, pure vector retrieval starts to feel like trying to solve a criminal case by searching for similar paragraphs.

You might find the right page.

But you will miss the network.

In the project we discussed internally, the client didn’t want “answers”. They wanted analysis. They wanted conclusions that weren’t written anywhere directly, but could be derived when you connect facts across multiple sources. That’s the point where knowledge needs to stop being a pile of text and start becoming a structured map.

And this is exactly where ontology shows up as a business tool, not a research topic.

At that point, something important became clear.

Hallucination was not the core problem.

The real issue was unbounded meaning.

The system was not inventing facts out of thin air. It was reasoning over connections whose meaning had never been clearly defined. When everything is allowed to mean anything, the model does not become smarter. It becomes confidently misleading.

Ontology, in practice, is how you put boundaries around meaning before you ask the system to reason on top of it.

Because once you start building graphs, you hit the next problem: freedom creates noise.

At some point, the team tried giving the system more freedom. No constraints. No predefined structure. “Just extract everything and let the model figure it out.”

The result was not intelligence. It was noise.

Millions of meaningless nodes. Relationships without relevance. Context drowning signal. Costs rising as more and more text had to be fed into the model just to maintain accuracy.

As one of the engineers put it later, “At some point we realized the model wasn’t learning. It was just collecting junk faster than we could filter it.”

That line is funny, but also painfully accurate. It describes what happens when you let a model extract everything in the name of “completeness”. You don’t get knowledge. You get a landfill.

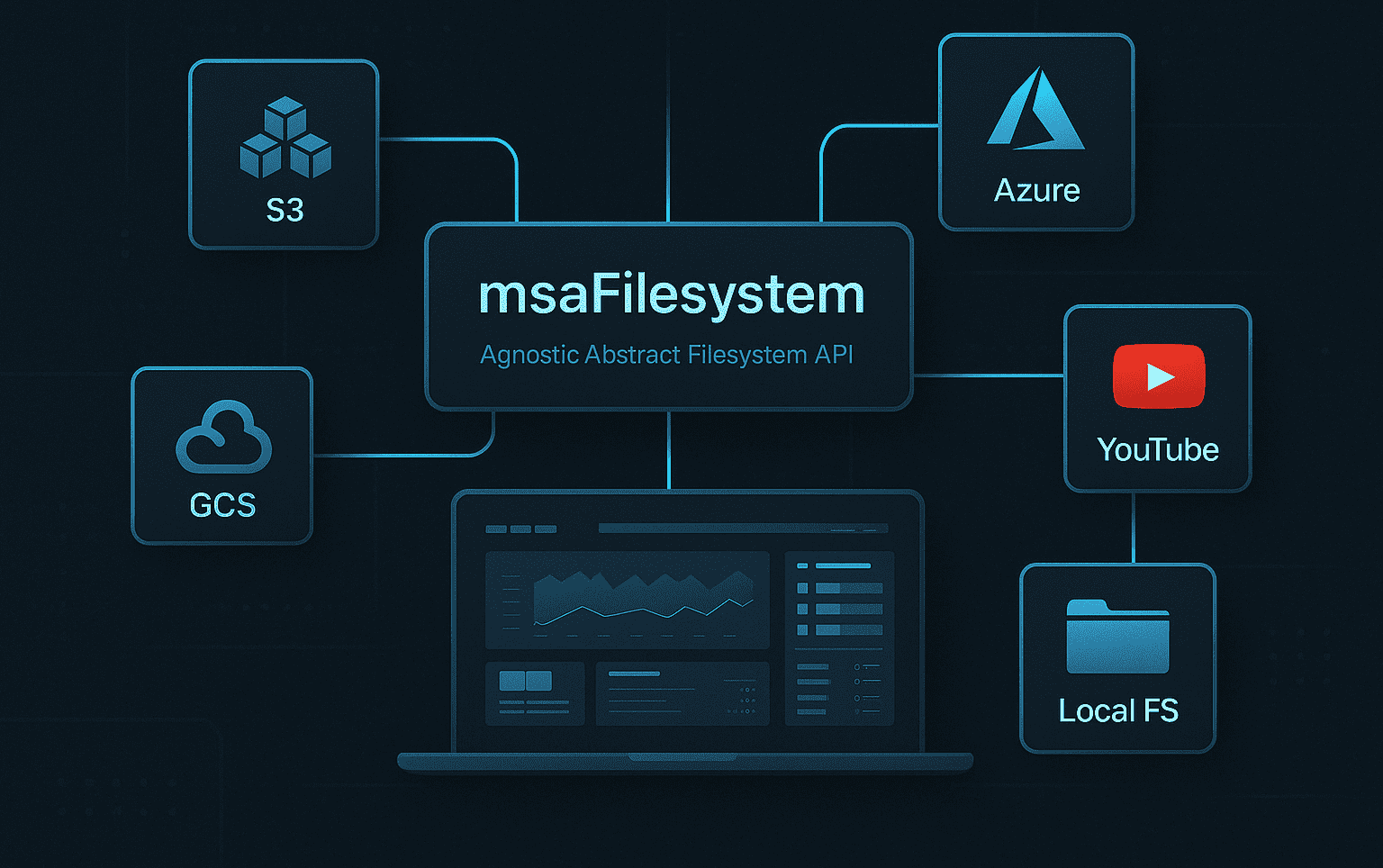

So they introduced a seed schema.

Not to restrict intelligence, but to give it boundaries. To decide what matters and what does not. In practical terms, it means you tell the system: these are the entity types we care about, these are the relations we care about, and these are the attributes worth capturing. You can expand later, but you don’t get to invent an entire universe from scratch.

This was a big deal because earlier approaches often throw documents into the pipeline and let the model define everything: what an entity is, what the schema is called, what attributes exist. It sounds flexible, but in production it increases hallucinations and makes quality control almost impossible.

In this project, the seed schema approach meant the extraction agent wasn’t guessing. It was extracting in a controlled way. That alone reduces hallucinations and improves graph quality.

But the more interesting part is what happened after the graph existed.

A graph is not just nodes. It is meaning.

And meaning breaks in unexpected places.

One of the most annoying real-world problems they hit was negation, cancellation, and “almost happened” events.

Humans read a sentence like “the transaction was canceled” and treat it as a non-event.

A graph often records it as a relationship anyway because the relationship exists in the text, even if the attribute says it’s negative. Then during retrieval and reasoning, that cancellation attribute gets ignored, and the system treats the mere existence of the edge as evidence.

So the AI “connects” things that should not be connected.

This is one of those uncomfortable details that separates demos from production. It’s not a model problem. It’s a meaning problem.

Project managers described the whole thing differently. From their perspective, nothing “technical” happened. What changed was the conversation with clients. Fewer explanations. Fewer “it’s not a bug” discussions. Fewer moments where the AI was technically right but practically useless.

Ontology, in other words, didn’t just change the system.

It changed trust.

This is the part I think founders need to hear clearly.

Ontology is not for everyone.

If you need a chatbot, a FAQ system, or a simple document search, you do not need ontology. You will waste time and money. There is no heroism in overengineering.

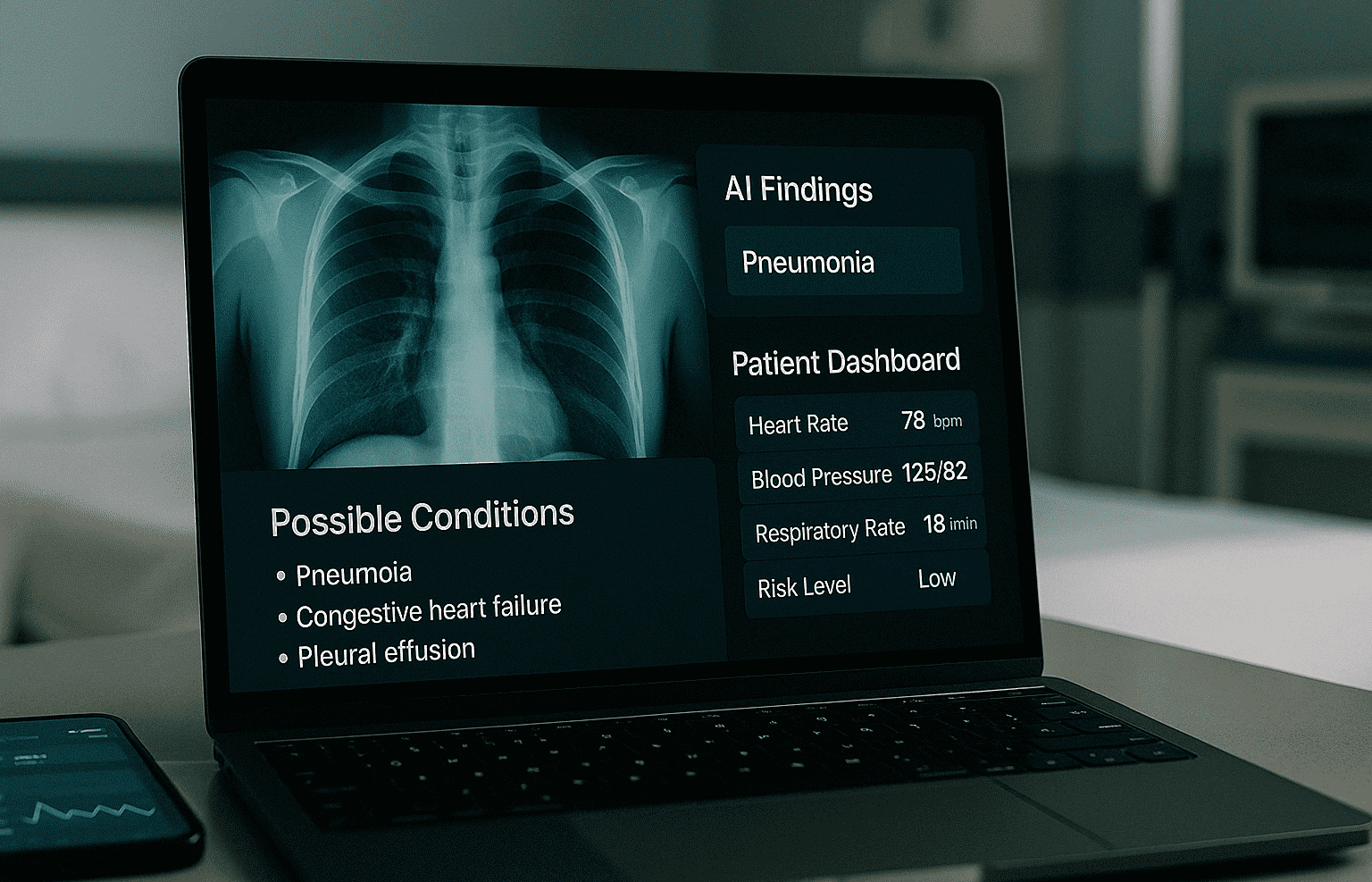

But if your AI system analyzes information, connects data across sources, influences decisions, or operates in domains where mistakes are expensive, then ontology stops being optional. Especially when AI moves from “supporting humans” to “advising them”.

Because once AI becomes agentic, “meaning” stops being documentation. It becomes executable instruction. It becomes the difference between automation that helps and automation that quietly damages workflows.

I’ve also noticed a shift in how serious platforms talk about this. Less “tables and columns”, more “business objects and actions”. Not because SQL is dead, but because agents don’t operate on rows. They operate on entities, relationships, states, and rules. That’s ontology thinking, whether people use the word or not.

And the thing that surprised me most is that ontology turned out not to be about technology at all.

It is about alignment.

Alignment between teams.

Between definitions.

Between assumptions everyone believes are shared, but rarely are.

Ontology is the moment a company stops assuming that everyone means the same thing by the same word, and decides to encode it.

That is why we now work with ontology in some of our AI projects. Not as a buzzword, not as a checkbox, and not everywhere. We start small. MVPs. Minimal structure. Just enough to stop the system from guessing.

Because guessing is expensive. Quietly expensive.

I did not write this article as an expert. I wrote it as someone who was asked to explain something he did not fully understand, and who decided to listen instead of pretending. If you are a founder or CTO and feel that your AI system is already working, but you would hesitate to base a real decision on it, that hesitation is not a weakness. It is usually the first signal that meaning has not been fixed yet.

Sometimes it means the model needs tuning.

Sometimes it means the data needs cleanup.

And sometimes it means the system simply does not share a clear understanding of what things mean.

So the real question is:

Would you trust this system to make a real business decision tomorrow?

If you want to talk through whether ontology makes sense for your AI architecture, or whether it would be unnecessary complexity at your current stage, we’re happy to have that conversation.

No demos.

No buzzwords.

Just a practical discussion about your use case, your data, and your constraints.

If you want to explore whether ontology makes sense for your AI architecture, I’m always open to a thoughtful conversation.